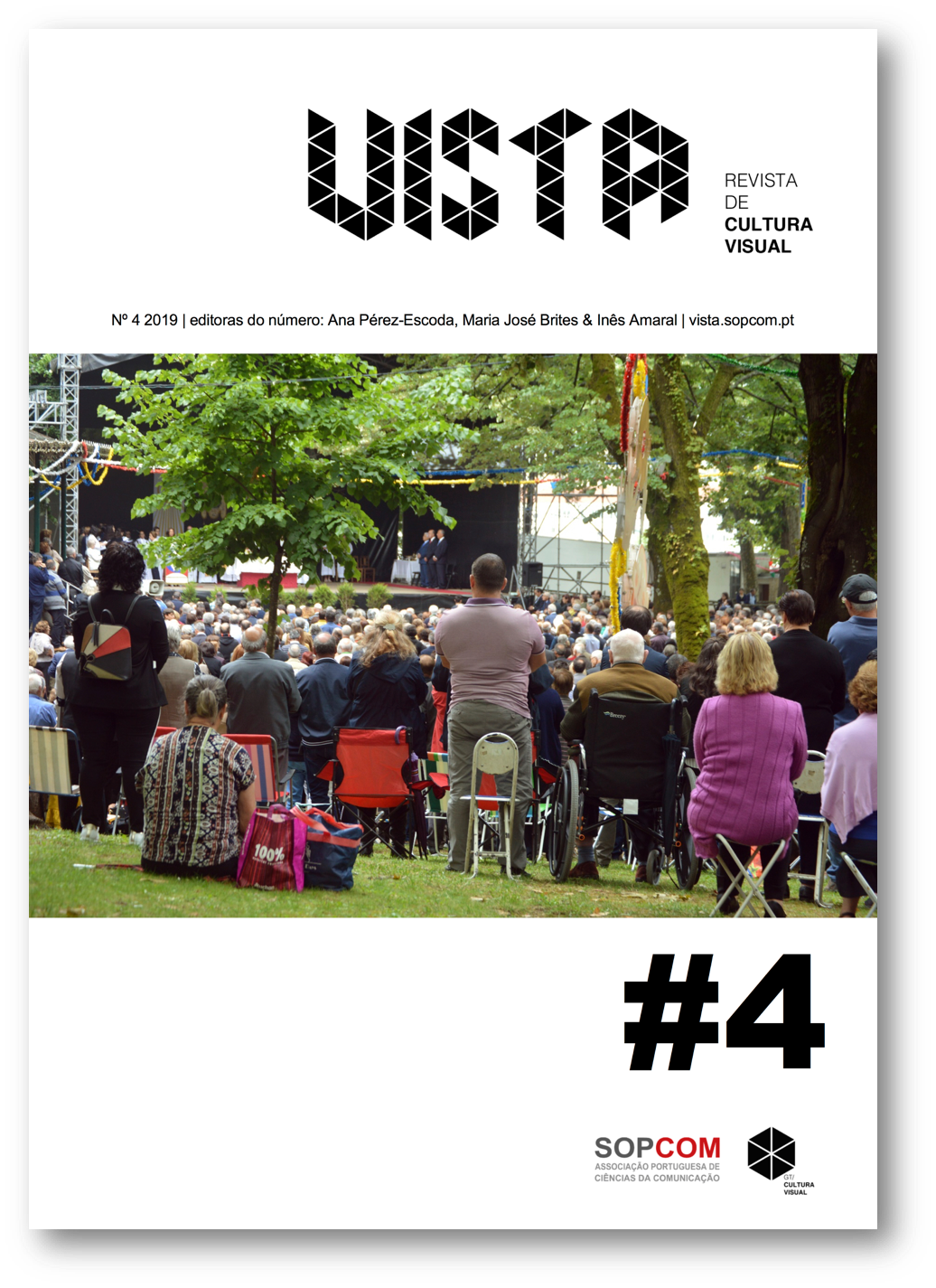

The selfie generation: a transformation of visual social relationships

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.3019Keywords:

visual, space, performance, proximity, intimacy, photography, visual communication, mobile technologyAbstract

The selfie generation is a term commonly used to describe people born after 1981 because of the supposed proliferation of selfies they take daily. If Selfies indeed define a generation of people, then they require close consideration as an evolution of social interaction. This interdisciplinary study focuses on photography as performance of looking involving social relationships between people. I ask “How might selfies suggest a transformation of everyday social relationships?” The selfie as active photographic performance is first examined through illustrative ethnographic observation. Then as performative photographic object the selfie is examined as interactive (Kress & Van Leeuwen’s, 2006, 2009) visual communication. Finally, the performative spaces of the selfie in process (from initial performance, to object and as it is shared and moves between private and public spaces) is examined as relationships of proxemic perception (Hall, 1966). For the selfie generation the private spaces in social relationships has perhaps evolved not simply because of changes in photographic technology, but also new spaces of socialising where private and public contexts are often blurred and unfixed.

Downloads

References

Andreallo, F. (2017). The semeful sociability of digital memes; visual communication as active and interactive conversation. PhD thesis, University of Technology, Sydney. Retrieved from: https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/120273

Barthes, R. (1981). Camera Lucida. Reflections on photography. New York: Hill and Wang.

Baym, N., & Senft, T. (2015). What does the selfie say? Investigating the global phenomenon, International Journal of Communication, 9,1588-606.

Burgess, J. (2007). Vernacular creativity and New media PhD Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Queensland, Australia.

Farman, J. (2012). Mobile interface theory; embodied space and locative media. New York: Routledge.

Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and punish; the birth of the prison (‘Panopticism’). New York: Vintage.

Frosh, P. (2001). The public eye and the citizen-voyeur; Photography as a performance of power. Social semiotics, 11(1), 43-59.

Frosh, P. (2015). The gestural image: the selfie, photography theory, and kinesthetic sociability. International Journal of Communication, 9, 607-28.

Ehn, P., Binder, T., Eriksen, M. A., Jacucci, G., Kuutti, K., Linde, P., & De Michelis, G. (2007). Opening the digital box for design work: supporting performative interactions, using inspirational materials and configuring of place (pp 50–76), in Streitz et al. (eds). The disappearing computer: interaction design, system infrastructures and applications for smart environments. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer.

Fischer-Lichte, E. (2008a). Sense and sensation: exploring the interplay between the semiotic and performative dimensions of theatre. Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, 22(2), 69–81.

Fischer-Lichte, E. (2008b). The transformative power of performance: a new aesthetics. London: Routledge.

Haggerty, K. (2006). Tear down the walls: On demolishing the panopticon, in Lyon (ed.). Theorising surveillance: The panopticon and beyond (pp. 23-45), Willan Press.

Hall, E. (1966). The hidden dimension. Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

Highfield, T., & Leaver, T. (2016). Instagramatics & digital methods; studying visual social media, from selfies and GIF to memes and emoji. Communication Research and Practice, 2(1), 47-62.

Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse: the modes and media of contemporary communication. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2006 [1996]), Reading images. The grammar of visual design. New York: Routledge.

Mann, S. (2004). Sousveillance: Inverse Surveillance in Multimedia Imaging. In Proceedings of the 12th annual ACM international conference on Multimedia (pp. 620- 627). ACM.

Markham, A. (2009). How can qualitative researchers produce work that is meaningful across time, space and culture?, in Baym & Markham (Eds.). Internet Inquiry, Conversations about Method (pp. 131-155). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Metz, C. (1974). Film, Language; a semiotics of cinema, trans. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mulvey, L. (1981)., ‘Afterthoughts. In Visual and other pleasures (pp. 29-38). Palgrave Macmillan, London.on ‘Visual pleasure and Narrative cinema ‘Inspired by King Vidor’s Duel in the sun (1946)’, Visual and other pleasures, pp. 29-38.

Mulvey, L. (1989). Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. In Visual and other pleasures (pp. 14-26). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mitchell, W.J.T. (1994). Picture theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mitchell, W.J.T. (2013). Showing seeing: a critique of visual culture, in Mirzoeff (ed.). The visual culture reader (pp. 86-101), London/New York: Routledge.

Monahan, T. (Ed.). (2006). Surveillance and security: Technological politics and power in everyday life. Taylor & Francis.

Pollock, G. (2018). Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity. In N. Broude & M. Garrard (eds), The Expanding Discourse (pp. 244-267). London: Routledge.

Sekula, A. (1989). The body and the archive, in Bolton (ed.). The contest of meaning; critical histories of photography (pp. 342-88), Cambridge: MIT press.

Warfield, K. (2015) ‘Why I love selfies and you should too (damn it)’, paper presented to the Public lecture at Kwantlen Polytechnic University, 26 March 2014. Published on YouTube, 2 April 2014. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aOVIJwy3nVo.

Williamson J., Hansen, L. Jacussi, G., Light, L., & Reeves, S. (2014). Understanding performative interactions in public settings. London: Springer verlag.

Zappavigna, M. (2016). Social media photography; construing subjectivity in instagram images. Visual communication, 15(3), 1-22.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Authors own the copyright, providing the journal with the right of first publication. The work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.